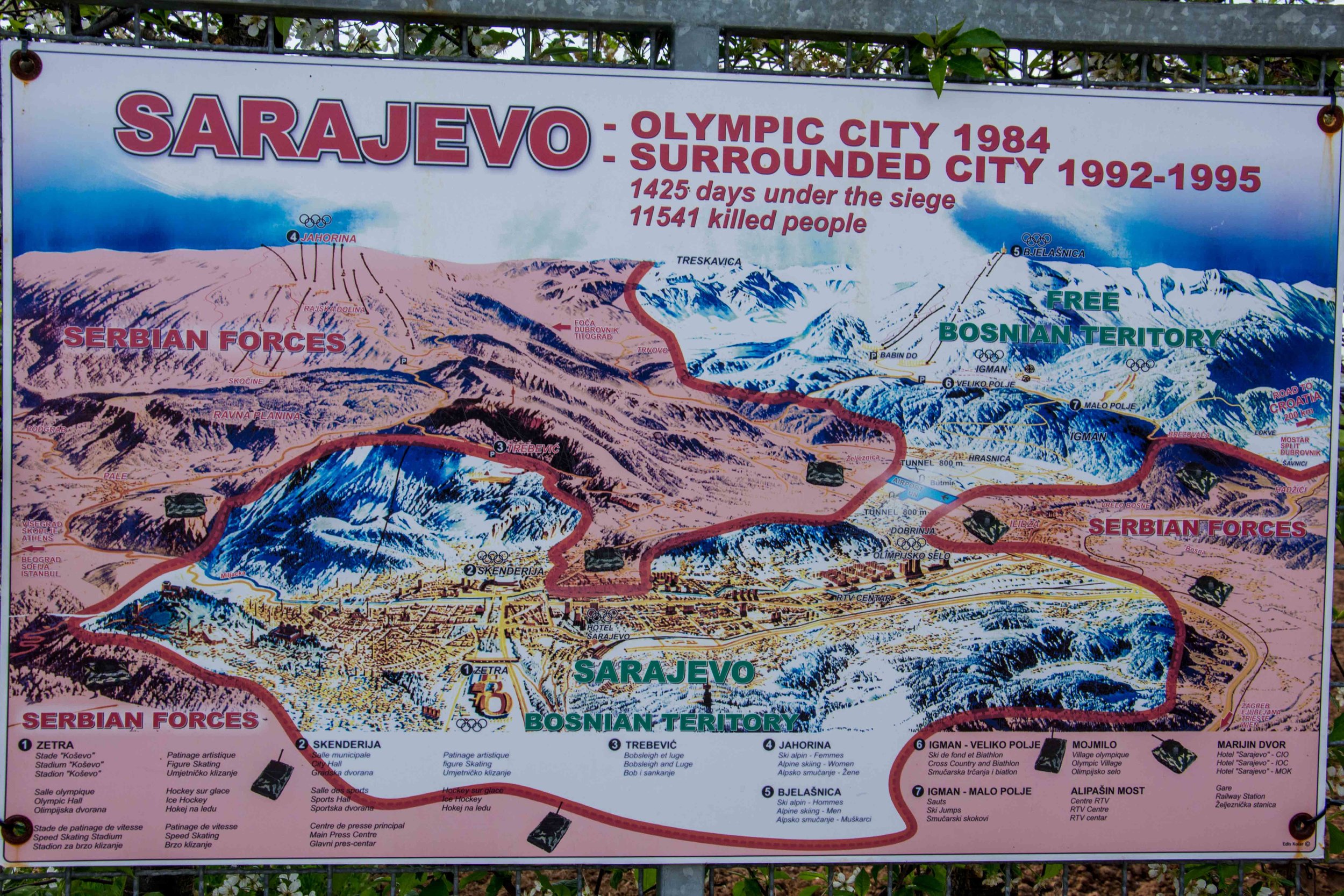

Sarajevo is a special place. All Sarajevans will tell you this. They survived the siege Serbian army for 1425 days from April 1992 to February 1996 during which over 5400 civilians were killed. But don’t forget its earlier history. Sarajevo was the city where archduke Ferdinand was assassinated which led to World War 1. The action is commemorated by a plaque at the corner where the assassin stood.

The plaque reads “ From this place on 28 June 1914 Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia.

We stayed in a small hotel on the outskirts of the old city and were able to walk directly into the old city a few metres away. A very basic hotel but perfectly satisfactory; after all we only slept there and needed nothing more. The old city was packed with tourists from what seemed to be every nation in the world, or at least the shopping areas were. We did not spend much of our limited time there.

The Old City is largely pedestrianised and has been substantially renovated since the war ended.

We did visit an exhibition at a centre known simply as the “Gallery 11/07/95” devoted to the events and genocide of Srebrenica. This was excellent but also deeply shocking. We both felt similar emotions to those we had experienced when we visited the Tuol Sleng museum in Phnom Phen. In the face of the enormity of the suffering and crimes of the war it managed to bring home the individual experiences of the victims. Except for one notable omission, about which more at the end. We had intended to go to the museum of Crimes against Humanity and Genocide as well, but the experience of Gallery 11/07/95 left us unable to face yet more horror and we spent the rest of our time exploring Sarajevo itself.

Many buildings still display war damage, while there are many new buildings (background) as well

The best thing we did was to take part in a “free” tour of the city with a young man as our guide. Free in the sense that at the end you only paid what you felt the tour was worth. The guide was 7 years old at the start of the siege and had grown up during the siege. He took us on a walk through the city visiting sites where incidents had taken place during the siege. It was a very good tour and his excellent narration gave real insight into how people had lived and survived.

The map shows clearly how the city was surrounded, but note the gap which is the airport where the tunnel was built.

During the war the city was under almost continual bombardment by the Serbian forces, using mortars and shelling, but also snipers from the areas they had managed to occupy. One of grimmer memorials are the remains of mortar explosions; wherever people were killed the shallow holes and shrapnel marks remaining were filled with red resin. These are known as “Sarajevo roses” and are found across the city.

Sarajevo Roses mark the spot where a mortar exploded killing people.

This one was of a mortar that exploded in the crowded open-air market and killed 68 people and wounded over 200. The UN observers recorded an average of 329 shell impacts per day during the siege, with a maximum of 3,777 on 22 July 1993.

Over 1500 children were killed during the siege and more than 15000 wounded. There is a moving memorial inscribed with the names of 521 Bosniak, Serb, Croat, Roma and Jewish children killed during the siege.

The names of 500+ children killed during the war. It is not a complete list by any means

Alongside it is a beautiful glass memorial to all the dead. The sculpture represents a mother protecting her child.

The second part of the Children’s Memorial, the Mother and Child.

Our guide told us he was 7 years old at the start of the siege. The day the siege started his mother took him down to the basement telling him that they were going on a camping trip in the basement. After about 2 weeks he began to feel that there was something wrong and that his mother might not be telling him the truth.

Even today there are many areas that have still not been fully repaired and many buildings are still pockmarked with bullet and shrapnel holes.

The building from which the tunnel under the airport was constructed.

Of course, we had to visit the famous tunnel under the airport. This was dug by hand during the siege as a way of getting goods into the besieged city. The airport was controlled by the UN and it was felt that this would give protection to the tunnel. It is 800 metres long and dips toward the centre so as to avoid collapse from the weight above it.

Narrow and low, the tunnel was the only access for the citizens of Sarajevo to the outside world.

It is not high so that you have to walk bending over through it. People brought in eggs and other foods through it. This benefited the “black marketeers” who were able to thrive, and the citizens who were able to get some supplies if they could afford it. It was designed by an engineer and had pipes to ventilate the shaft, electricity cables and a pump to pump water out. It really is an amazingly resourceful piece of engineering.

After the visit to the tunnel we enjoyed a cold beer at an old pub where we observed the local youth behaving like youngsters around the world.

Selfies everywhere!

After Sarajevo we travelled on to Tuzla where we stayed with Ursula’s work colleague Mihela for a couple of days and collected our “lost” luggage. Tuzla was a destination for refugees fleeing Srebenica during the war. It was never occupied by the Serbs and remained a safe haven, particularly for the men who managed to escape Srebenica and walked the 120 km or so through the forests and mountains. This journey took at least a week and many were killed along the way by the Serbs and Chetniks. There are still displaced families staying in what remains of the refugee camps around Tuzla.

View over Tuzla from a hill overlooking the city.

Summing Up.

Our feelings after visiting Bosnia and Croatia. We found memories of the war still very much alive. Signs of the war, the shattered buildings and in people’s recollections both shocking and impressive. There seems to be so much potential for the country if it could get over its past. Essentially the Serbs are still fighting the Ottoman Empire and Islam although they were essentially independent of the Ottoman by the early 1800s. But like the Irish, history runs very deep.

There still seems to be some fear that the violence could break out again, that things are not really settled yet. For instance, schools in many areas have separate classes for Christians and Muslims, and as I mentioned earlier, there is fear that the Serbian administration is re-arming under the pretext of building up its police.

One thing we did notice and which we commented on to each other was the portrayal of women in the war. They were very much shown as victims grieving for their lost menfolk and male children. Nowhere did we see any reference to the ordeals suffered by them, in particular the mass rapes. It might be that in such a short visit we simply missed the relevant documentation, but we doubt it. It seems something that people are unwilling to face up to.

In Croatia there is less openness about the war, but if we asked questions, the people we spoke to were quite open. But we saw only a tiny part of Croatia, Dubrovnik and the surrounding area. It is a country we would love to go back to and explore further if we ever have the time.

And then, united with our luggage again, we flew back to Switzerland to prepare for Ethiopia.